Lars in Japan

The 1964 Olympics were the dawn of a new world for Japan. In 2021, the magic of that time should have been repeated. But the games took place in empty stadiums, and travelers couldn't enter the country. I, too, had to exercise patience. As consolation, I cling to good memories, some of which I summarize here.

Image: Shizuko Yoshikawa, Axis Gallery, Tokyo, 2018 ©Lars Müller

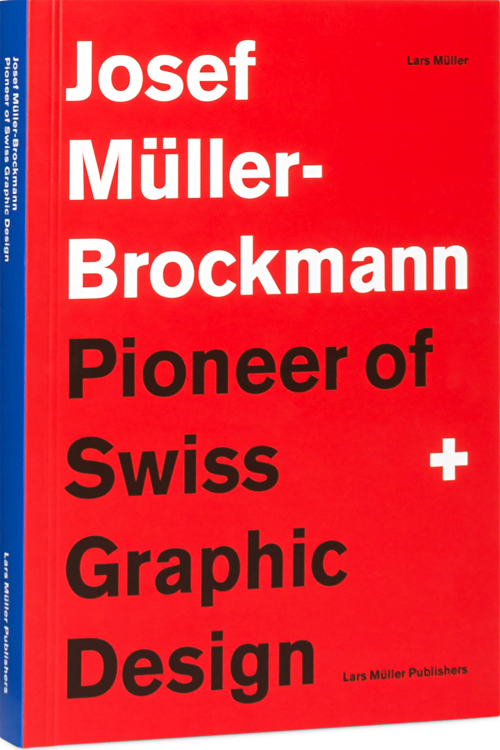

Until the end of the 1990s, Japan was far away and only one of many markets for the publishing house. An increasing interest in my books then became noticeable in 1996 upon the death of Josef Müller-Brockmann, who was highly regarded as a designer in Japan since the 1960s. The Japanese became aware of me through my publication Josef Müller-Brockmann. Pioneer of Swiss Graphic Design in 1995. And in return, Müller-Brockmann’s widow, Shizuko Yoshikawa, sparked my interest in Japan.

Product designer Jasper Morrison, who often does work for Japanese companies, gave me a good reason to travel to Japan for the first time in 2003. In 2006, I collaborated with him and Naoto Fukasawa on the brochure Super Normal for the first exhibition in Tokyo and then presented it as a book at the Triennale in Milan in 2007.

Image: Lars Müller, Zürich, 2021 ©Lars Müller

Helvetica – Homage to a Typeface, first published in 2002, launched a veritable hype in Japan. The Japanese had developed a penchant for the Swiss Style in graphic design. In 2009, the exhibition “Helvetica Forever” was shown at the Ginza Graphic Gallery (GGG) in Tokyo.

In 2021, the Japanese fashion brand Comme des Garçons celebrated the typeface Helvetica on a sports jacket.

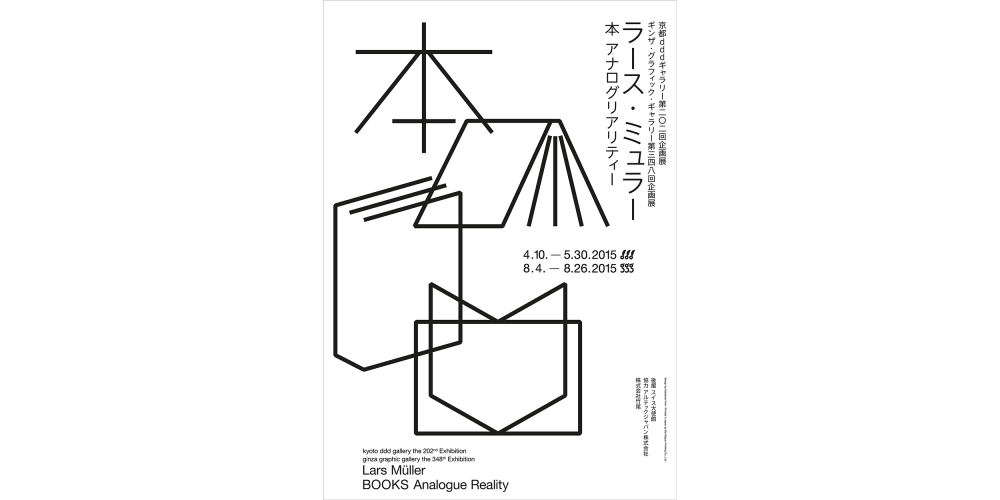

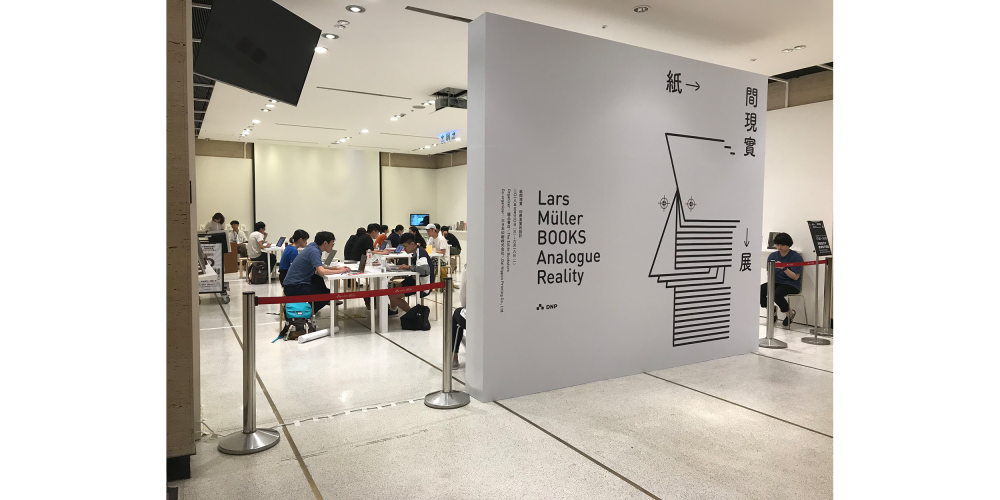

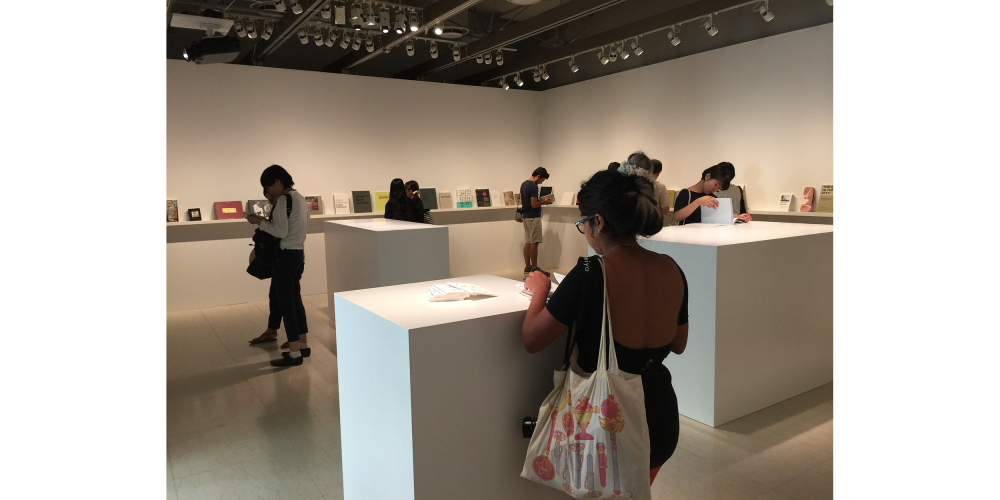

My exhibition “Analogue Reality” was then on view at GGG in 2015 after being shown in Kyoto and later in Shanghai and Taipei. Relationships have grown. When you show interest in people and where they live, the other side usually responds in kind and new projects are born. In this way, my interest in Japanese architects and their work resulted in publications like Shift. SANAA and the New Museum in 2008, Insular Insight about the Art House Project on Naoshima Island with Akiko Miki and Iwan Baan in 2012, and on Tange, Kikutake and Shinohara with the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

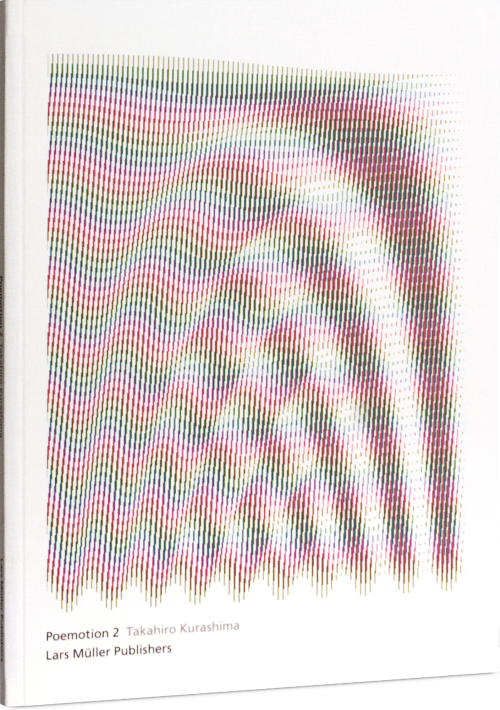

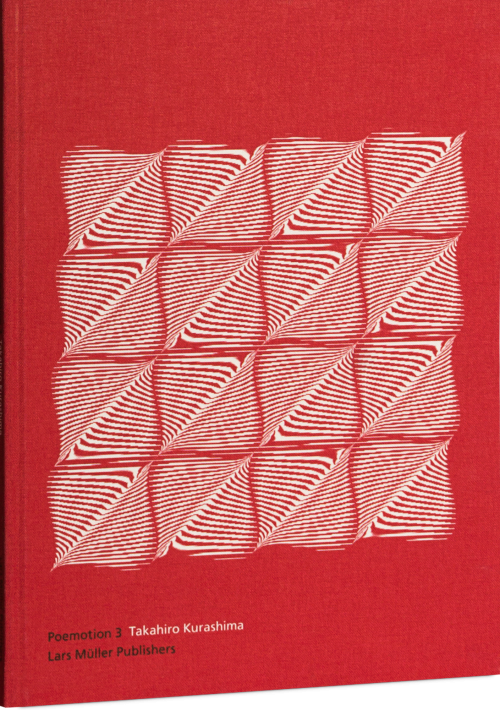

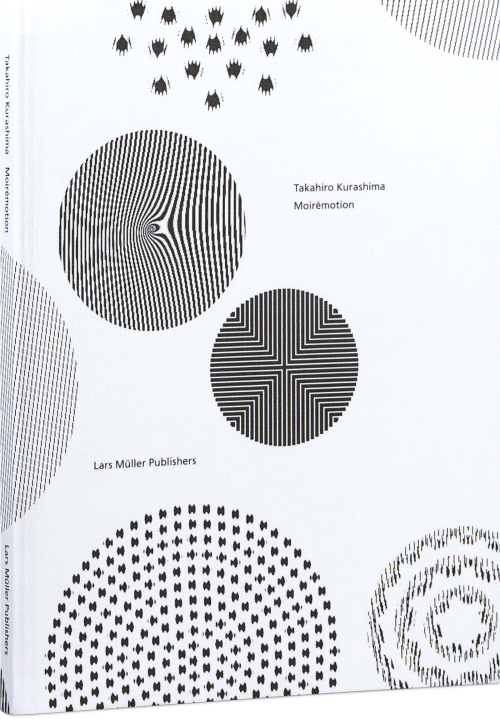

Image: Takahiro Kurashima, Tokyo Art Book Fair, 2017 ©Lars Müller

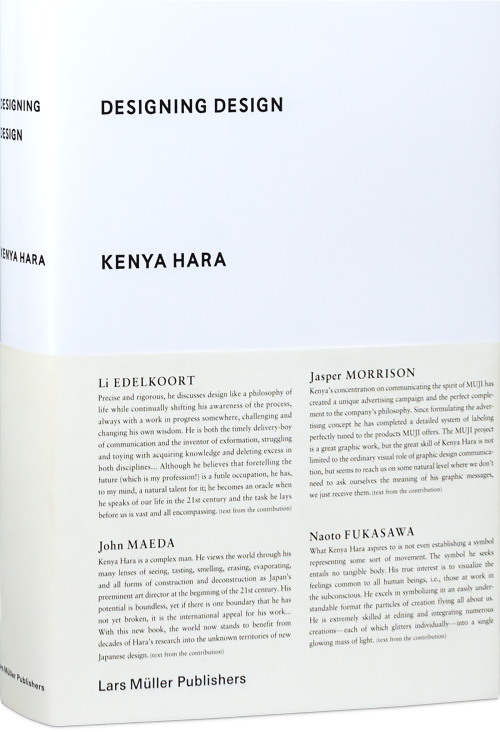

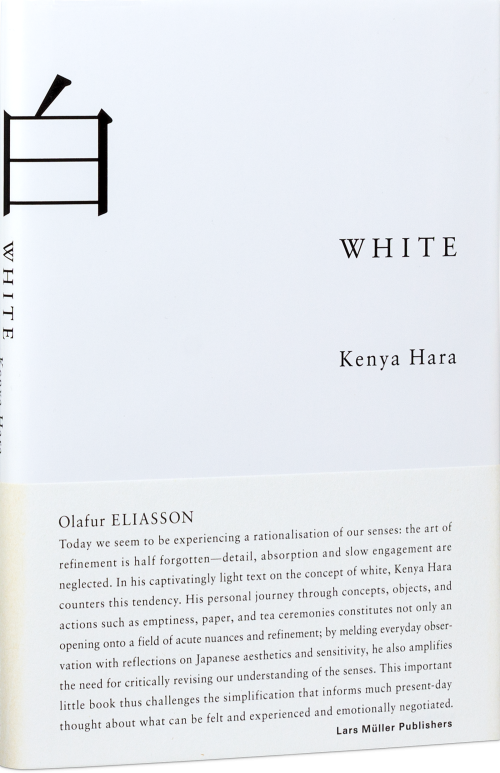

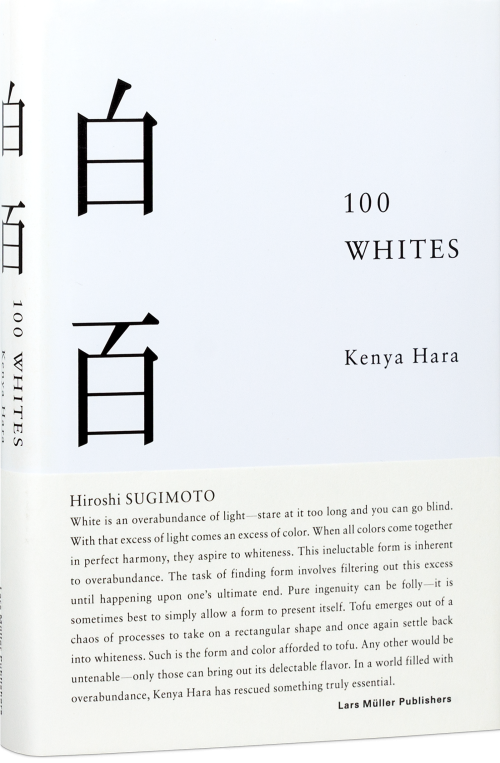

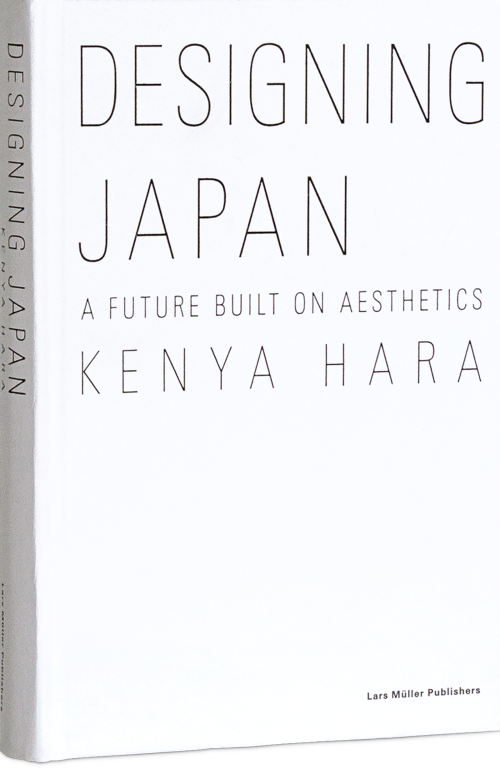

Also in 2012, Takahiro Kurashima approached me with a proposal for Poemotion, which became a huge success worldwide, published in three volumes. And of course there is also Kenya Hara, whose Designing Design, first published in 2007, broke all records and brought him international fame. In the small volume White, published in 2008, he sets out his philosophy of emptiness, a source of inspiration for designers and many others. We have published five books together so far, and there are more to come.

Our mutual interests, in my opinion, came about because of a constructive misunderstanding. Japanese aesthetics are striking in their simplicity and attention to detail, influenced by Zen Buddhism. Instead of going nature one better, man-made objects are meant to form a contrast. Everything utilitarian is a transformation and moves away from nature. At the same time, this philosophy praises its magnificence.

In a Japanese teahouse, one finds nothing but the utensils required for the ceremony. Somewhere in the room, a small branch stands in a vase as a symbol of the perfection of nature. The simplicity of the Japanese world of forms has developed over centuries and is, as I like to put it, “heart-driven,” while in contrast Western modernism is rational and “brain-driven.” It has developed with industrialization, which necessarily brought with it a simplification of forms as industry sought to produce good products in large quantities and at a low price.

The Bauhaus radicalized this aesthetic, and Adolf Loos spoke of “ornament as crime.” European porcelain, for example, white and plain, resembled the Japanese aesthetic of simplicity. The worlds converged, for completely different reasons and with different roots. I believe that all people share the aesthetic instinct and the need for beauty and harmony, no matter where they are and despite culturally and historically different lines of development.

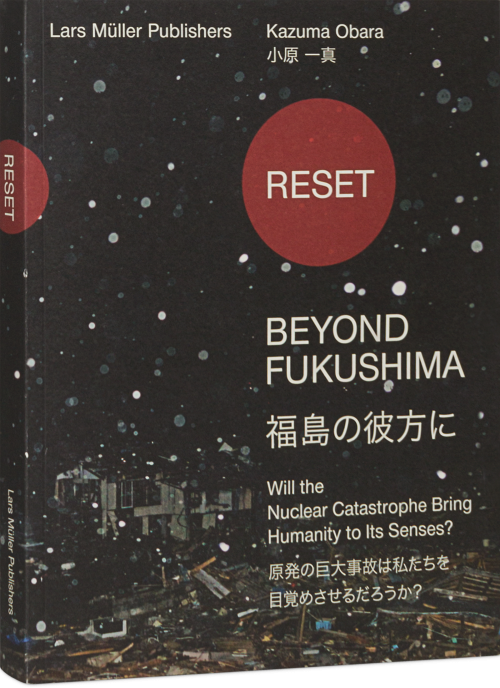

Shortly after the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, I documented the event and the brave first rescuers in a book I did with the photographer Kazuma Obara: Reset. Beyond Fukushima, 2011. I learned a lot about Japan and the nature of the Japanese in the process.

In 2018, the designer Helmut Schmid passed away in Osaka. He was a dear friend who, along with his daughter Nicole, was always there when I hosted something in Japan. Nicole was distraught and didn’t know what to do about Helmut’s studio in Osaka. I advised her not to throw anything away! I introduced her to the director of the Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Christian Brändle, who is a friend of mine.

Because Wolfgang Weingart’s estate is already in the museum’s collection, I thought it made sense that the work of Helmut Schmid, who like Weingart was a graduate of the Basel School, should also be housed there. We met in Helmut’s studio in the fall of 2019 with Nicole and Chikako Tatsuuma, who works for GGG Gallery and has been a loyal companion and advisor to me for years. Helmut Schmid often worked for the gallery and created beautiful exhibitions. We spent two days rummaging through the archive and found some of the things we were looking for, others not – but it was important that we could touch the items. Later, Barbara Junod, the curator of the museum’s graphic arts collection, traveled to Osaka and selected objects for her collection. My goal had been achieved.

Christian and I stayed in Kyoto, half an hour from Osaka, at the Hotel Enso Ango Tomi II, for whose library I had curated one hundred Swiss books. The hotel was designed by the Swiss firm “Atelier Oï,” whose partner Patrick Reymond once took me on a tour of Gifu Prefecture, where I was able to discover breathtaking crafts, from traditional swordsmithing to the production of razor-thin paper and the making of Isamu Noguchi’s famous Akari lamps.

Another reason for the 2019 Japan trip was the opening of the exhibition “What’s Karl Gerstner? Thinking in Motion” at GGG. An important focus of the exhibition was Gerstner’s publication Designing Programmes, 1964, which I reprinted. I was invited to the opening and combined my stay with other projects.

The exhibition opening was followed by a trip planned by Kenya Hara. We were driven to the airport bright and early, without me knowing where the trip would take me. We landed in Kagoshima Prefecture on the southern tip of Kyushu Island. Over the next few days, I visited two onsen and went on excursions. Staying in an onsen – a hot spring – is characterized by not doing anything. A physical standstill. “High Resolution Tour” is what Kenya calls his new concept. In contrast, mass tourism is “low resolution”. Kenya reacts to this with an itinerary of carefully selected places and sights that are absolutely exceptional, like the two onsen Tenku and Gajoen.

At noon I was shown my bungalow and told that I would be picked up in the evening. A steaming bath in a stone tub was waiting for me on the terrace. I got into the tub and looked out into the bamboo and cedar forest. A volcano smoked in the distance. The air was cold, the water red hot. After dinner, a seemingly endless culinary expedition, I lay in the tub again late at night and looked up at the starry sky. In Asia you can see constellations that you can’t see in Europe. A completely different cosmos presents itself.

The next day, bright and early, we hurried back to the airport and flew back to Tokyo, straight to the Nippon Design Center, Kenya Hara’s office, where a seminar on “100 Years of Bauhaus” was being held. This was an example of Kenya’s efficiency; I had been on the road for 72 hours and had experienced a lot – and came back to the greatest possible contrast: a seminar with eight speakers and an audience of 150 gathered to discuss the Bauhaus from noon to evening on a Sunday. I gave a half-hour talk on the Bauhaus from my perspective and introduced my books. My lecture was translated into Japanese – after which I understood next to nothing for the rest of the day.

Image: Shutaro Mukai, Tokyo, 2019 ©Lars Müller

To my knowledge, there were three Bauhaus students of Japanese origin. And many of the Bauhaus masters were attracted by Japanese aesthetics in architecture and object design and of course by the art of calligraphy. In Shutaro Mukai, I met a former student of the Ulm School of Design, which saw itself as the Bauhaus successor. Max Bill was its first director from 1953–55. Shizuko Yoshikawa came to Europe in 1961 to study at this school. It is rewarding to see in cultural exchange a positive side of globalization and to be curious about how people live in other places with similar conditions, having different concepts and ideas than our own. We know that the aging of Japanese society places unique demands on new technologies. For example, research is being done into robots that help people remain more mobile in their later years. Here, Japan is ahead of the rest of the world. Conversely, Japan needs to press ahead with opening up its society and overcoming the disadvantages of being an island. In comparison, Europeans are striving to preserve national and regional identities in the context of the continental community. It is best to keep the lines of communication open in both directions: in my books I bring Europe to Japan and a piece of Japan to the world. The book is uniquely suited as a modest, friendly, but determined impulse for this exchange between cultures.

Lars Müller, July 2021