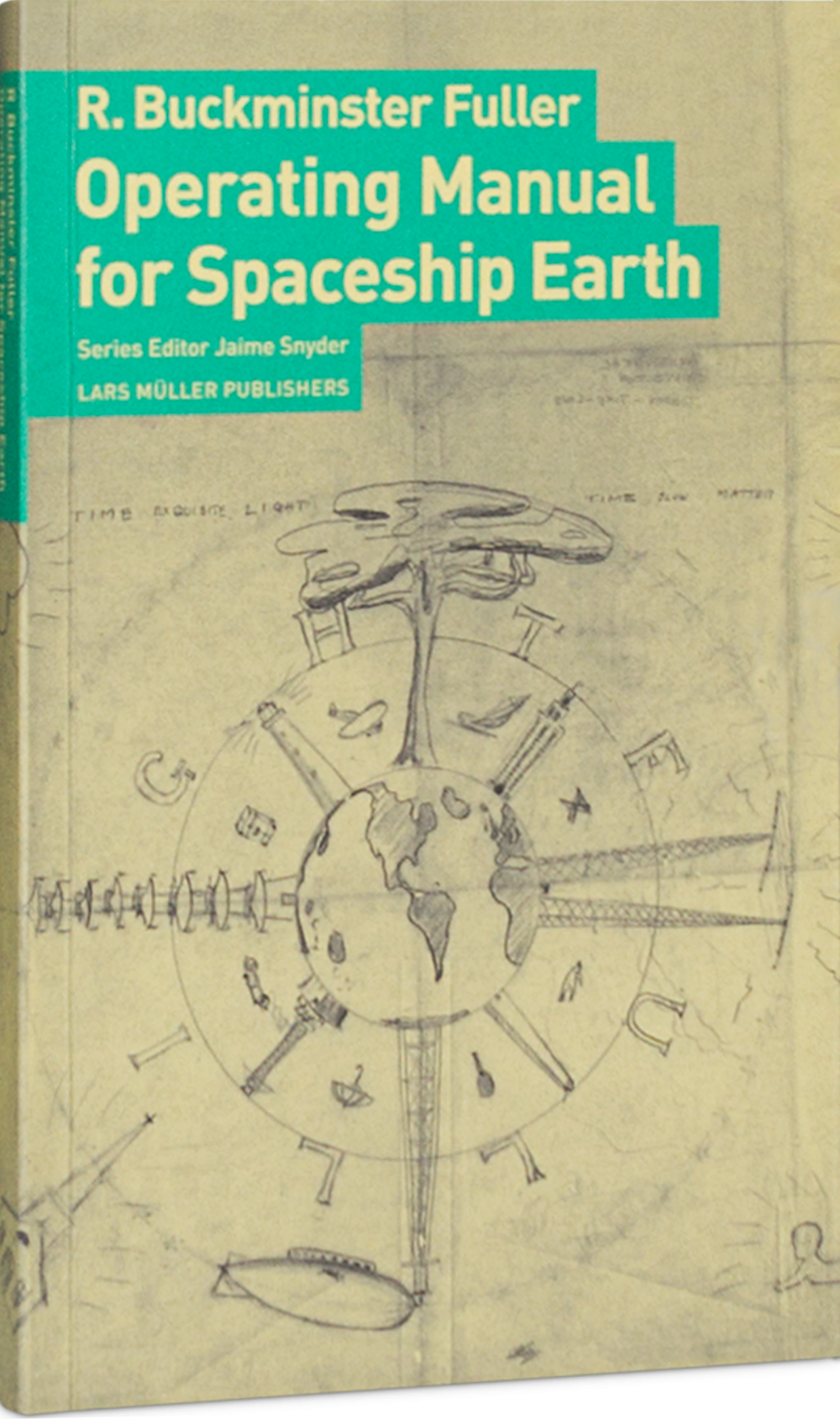

Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth

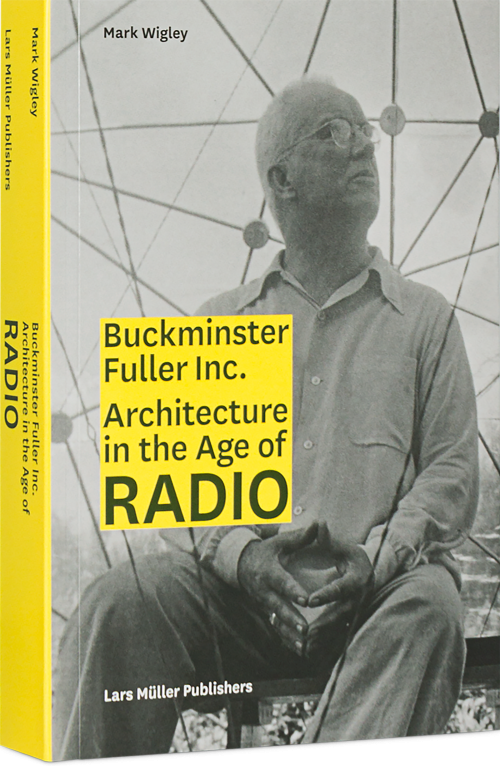

First published in 1969, "Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth" is one of Richard Buckminster Fuller’s most popular works and a brilliant synthesis of his world view. In this very accessible volume, he investigates the great challenges facing humanity: How will humanity survive? How does automation influence individualization? How can we utilize our resources more effectively to realize our potential to end poverty in this generation? Fuller questions the concept of specialization, calls for a design revolution of innovation, and offers advice on how to guide “spaceship earth” toward a sustainable future.

First published in 1969, "Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth" is one of Richard Buckminster Fuller’s most popular works and a brilliant synthesis of his world view. In this very accessible volume, he investigates the great challenges facing humanity: How will humanity survive? How does automation influence individualization? How can we utilize our resources more effectively to realize our potential to end poverty in this generation? Fuller questions the concept of specialization, calls for a design revolution of innovation, and offers advice on how to guide “spaceship earth” toward a sustainable future.

Chosen as one of the Top 50 Sustainability Books by the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL)