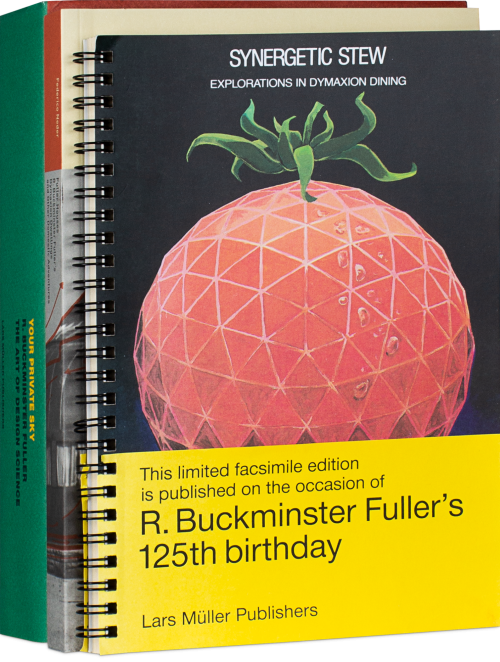

Your Private Sky

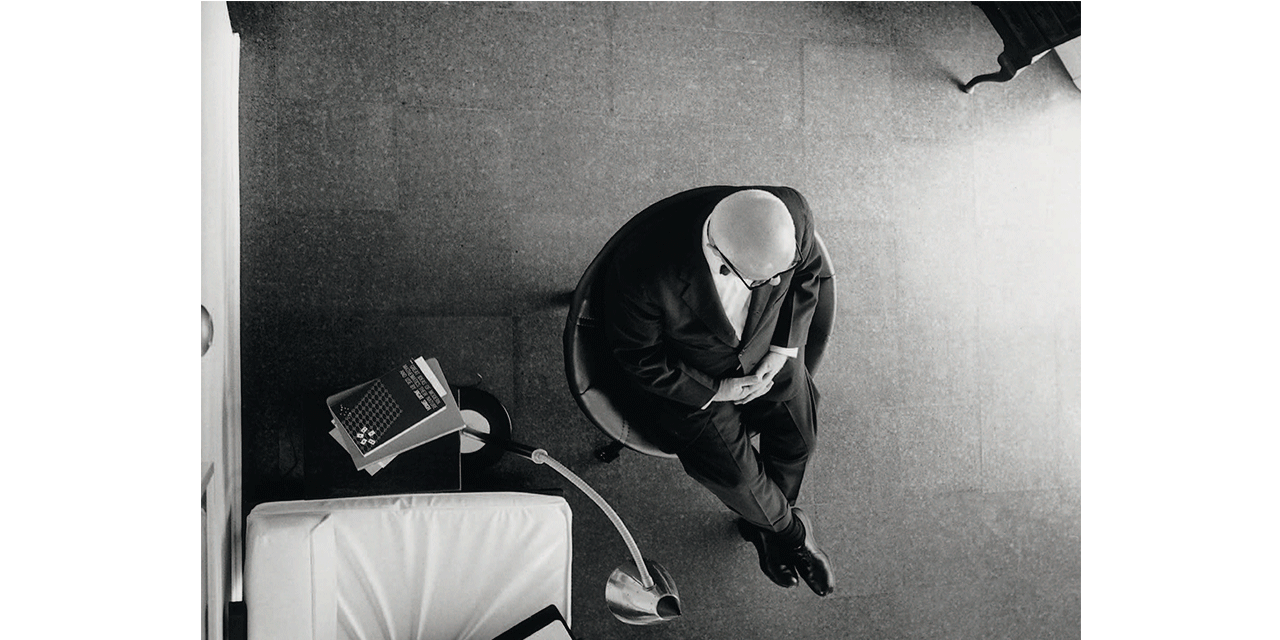

R. Buckminster Fuller

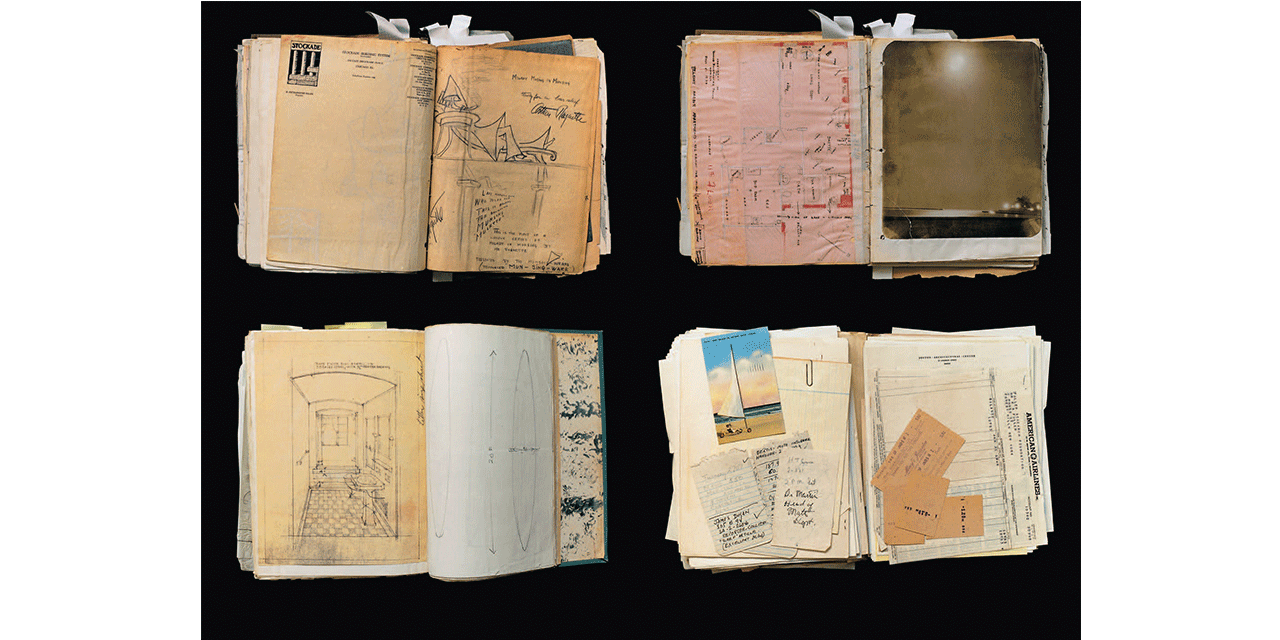

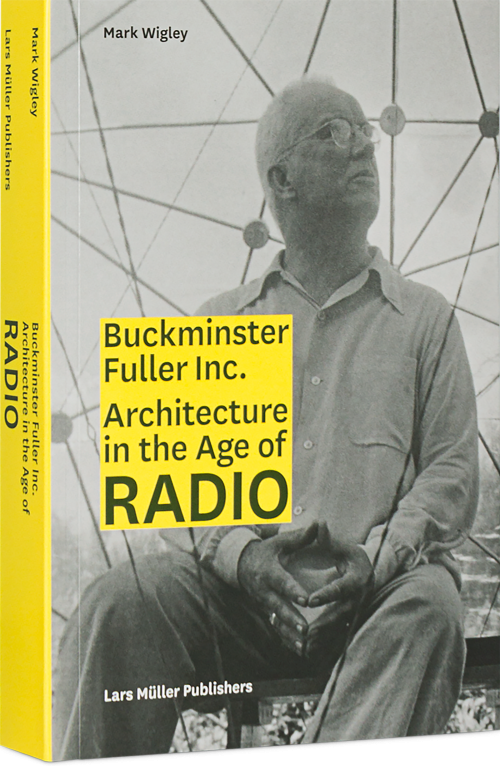

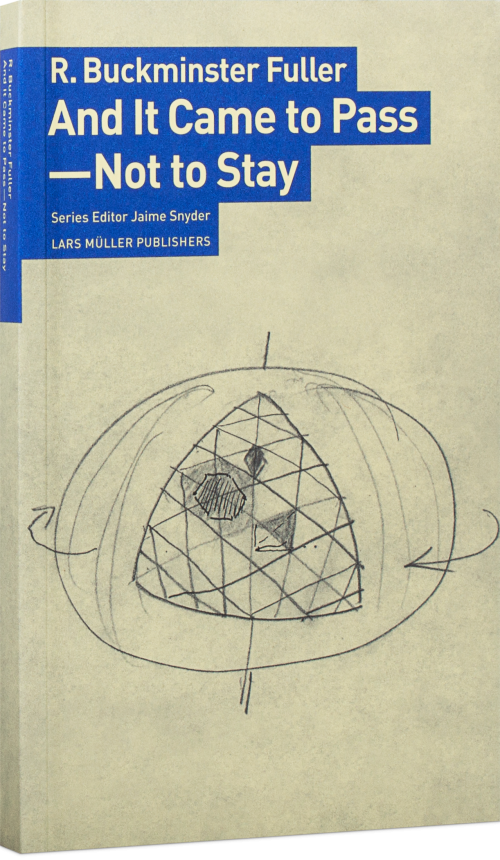

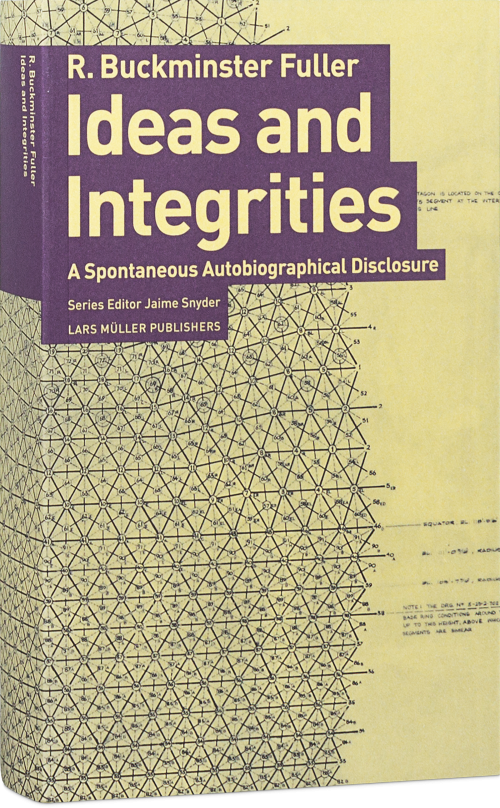

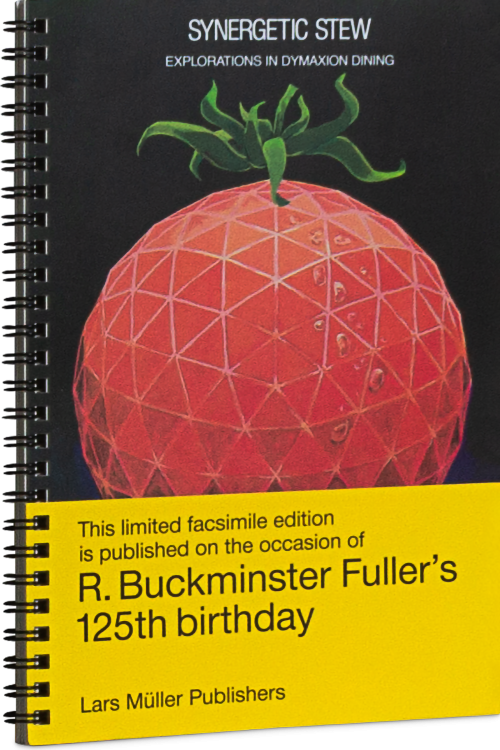

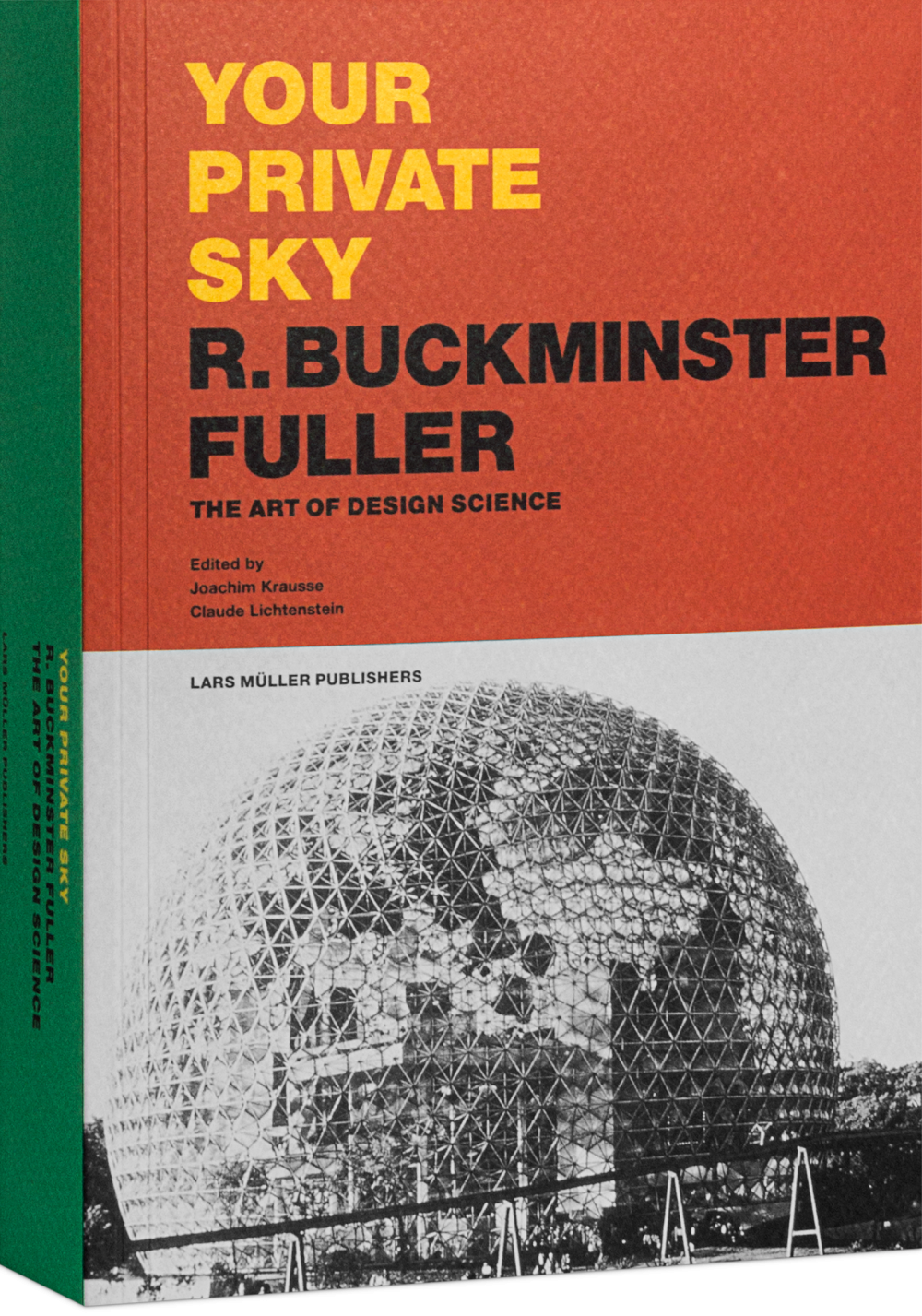

In light of the reawakening interest in R. Buckminster Fuller’s works and thoughts, and of their growing importance for our technological world, it is time for a reedition of this comprehensive and legendary publication from 1999. The visual reader Your Private Sky examines and documents Fuller’s theories, ideas and projects, and critically deals with his ideology of “rescue through technology.” This book provides a highly multifaceted insight into Fuller’s world, also showing many of its less known sides.

Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) was one of the most revolutionary technological visionaries of the 20th century. He established new standards that can be seen as decisive for future-capable design. “How to make the world work” – to this task he dedicated his unflagging attention. Convinced that specialists usually create more problems than they solve, he developed his concept for a vision of the whole.

As an architect, engineer, entrepreneur and poet, he was a quintessentially American self-made man. But he was also an outsider: a technologist with a poet’s imagination who already developed theories of environmental control in the thirties and who anticipated the globalization of our planet. Catchphrases of our time, like “Spaceship Earth”, “synergetic”, or “think global, act local” – can directly or indirectly be traced back to Bucky.

In light of the reawakening interest in R. Buckminster Fuller’s works and thoughts, and of their growing importance for our technological world, it is time for a reedition of this comprehensive and legendary publication from 1999. The visual reader Your Private Sky examines and documents Fuller’s theories, ideas and projects, and critically deals with his ideology of “rescue through technology.” This book provides a highly multifaceted insight into Fuller’s world, also showing many of its less known sides.

Buckminster Fuller (1895–1983) was one of the most revolutionary technological visionaries of the 20th century. He established new standards that can be seen as decisive for future-capable design. “How to make the world work” – to this task he dedicated his unflagging attention. Convinced that specialists usually create more problems than they solve, he developed his concept for a vision of the whole.

As an architect, engineer, entrepreneur and poet, he was a quintessentially American self-made man. But he was also an outsider: a technologist with a poet’s imagination who already developed theories of environmental control in the thirties and who anticipated the globalization of our planet. Catchphrases of our time, like “Spaceship Earth”, “synergetic”, or “think global, act local” – can directly or indirectly be traced back to Bucky.